The internal ride of making art and sharing it in public can be day-to-day at times.

I’ve got several months until my first solo photography show in June 2019, at Kreuser Gallery. The subject matter is in my hands. No pressure is put on me. I get to just be me and make the work I want to make. How amazing. How scary.

I photograph things near daily. Sometimes for myself, a fleeting moment of what grabbed me along a walk. Sometimes with focus and intention for project ideas. Sometimes, overlapping the two, I photograph to share via Instagram and Humanitou.

It’s different to shoot with creative expression wide open to me than when I made photographs for newspapers, magazines, ads, corporate needs. I’ve done it for a very long time. I have not always showed it.

I shoot what appeals to me in any given moment. Sometimes planned. Often not. Then, in time, I question if it will appeal to others. Worse yet, if it will be criticized. Oh, how often we censor ourselves preemptively.

In my braver, more objective moments an urge to fight and stand tall rises. In the less confident, more fragile moments I doubt. I fear.

And, if I wasn’t making daily practice of embracing all I am through yoga, I’d loathe and destroy myself inwardly. I’d shelve the work. That’s my history. It’s the history of how so many creative, feeling, thoughtful people treat themselves.

Still Lifes of the Me + Famous

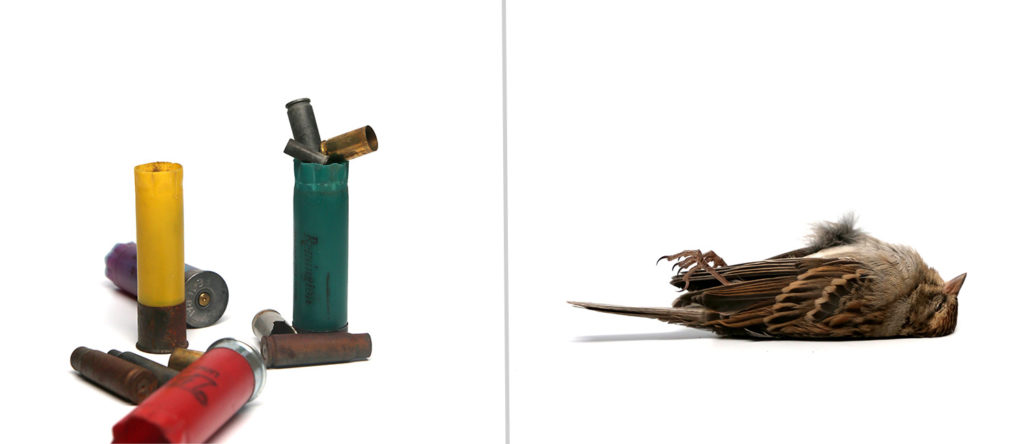

My photography project for the show next year is one of still lifes, or nature morte (“nature dead”). I’ve been shooting what I feel connected to, what I bring home from trail yoga sessions, breathing, seeing and contemplating in nature.

There is depth of message and meaning to me in this simple work.

And I love simplicity. I photograph the objects with a clean white background. No clutter. Visual poetry, lyrical efficiency. Space to breathe in the frame and direct all eyes.

Love simplicity. I’ve recognized it is a common thread through the most important things to me philosophically, spiritually, creatively … everythingly.

In part because of that anti-complexity, I sometimes fear sharing the work. My ego tells me what others will say, “It’s too simple … C’mon, I could do that … Why does this matter … Who cares?”

To ease some of that discomfort, I have been researching still lifes. I’ve found much of how and why I’ve been drawn to photography lies connected to — probably unwittingly influenced by — the history of so many others who’ve seen the world before me.

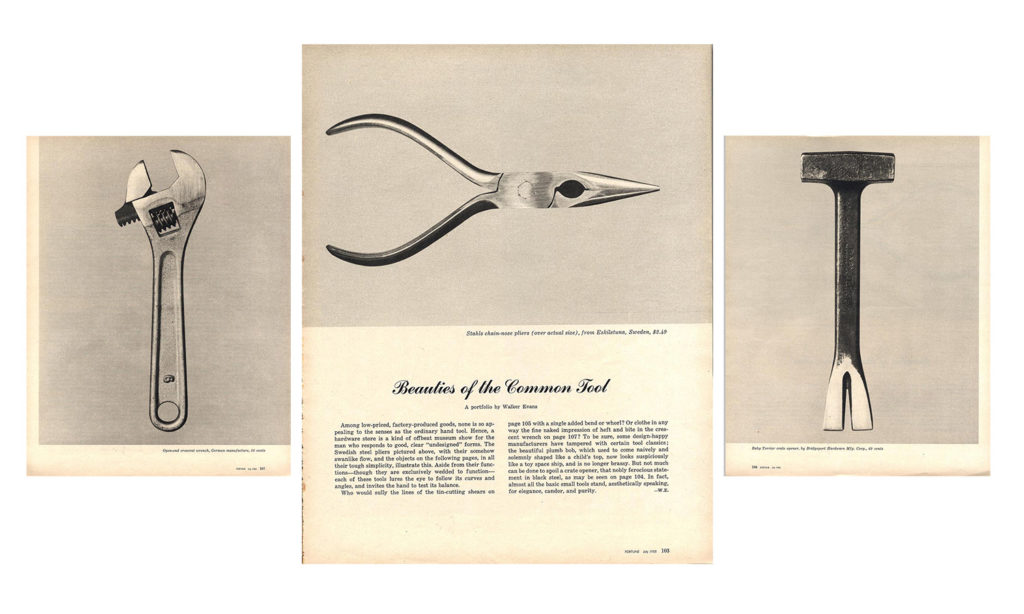

I’ve learned Walker Evans, of Farm Security Administration documentary photography renown, also made the simplest portraits of the simplest tools.

In intro to a portfolio of tool still lifes by Evans, published in Fortune in 1955, he wrote:

“Among low-priced, factory-produced goods, none is so appealing to the senses as the ordinary hand tool. Hence, a hardware store is a kind of offbeat museum show for the man who responds to good, clear, ‘undesigned’ forms.

“The Swedish steel pliers, with their swanlike flow, in all their tough simplicity, illustrate this. Aside from their functions … each of these tools lures the eye to follow the curves and angles. …

“Not much can be done to spoil a crate opener, that nobly ferocious statement in black steel. In fact, almost all the basic small tools stand, aesthetically speaking, for elegance, candor and purity.”

I’m also finding some kindredness with the famous fashion and portrait photographer Irving Penn. I’d known his portraiture. Encountering his still lifes resonates even more for me right now.

Penn, too, liked to bring the textured and dirty, wabi-sabi and even macabre into his studio, among other things, and make beauty from the otherwise overlooked and discarded. It seems he too favored a clean, simple image.

The list of resources and attaboy encouragements for me rolls on in the simple and still works of Imogen Cunningham, Edward Weston, Josef Sudek, André Kertész … and, I’m sure, countless more whose work I’ve yet to see.

These artists’ works — still lifes and other — have been and are in major galleries, collections and publications.

It’s a funny thing, the subjectivity of art, the curation of whose work gets the light and whose comes about in the shadows and never leaves them.

It factors into our own self-defeating voices when we’re in the throes of creating. It stirs the fears and the desires to seek validation, assurance that what we’re doing is at least in the realm of “It’s OK. You’re OK.”

I wish it wasn’t that way. Yet it is. And I know I’m not alone. No matter how many artists I feature in Humanitou conversations, artists whose work I admire, they all concede the emotional and psychological ride is there.

It probably has been for everyone who ever created. It’s part of the process. The hidden.

I’m unhiding it here, letting go of the weight.

Onward.