Alain Navaratne leans back on the family couch. Relaxed. His paintings hang on the wall behind him, and throughout the room. Alain’s most recently completed work, a bit larger than those on the walls, rests on a sizeable easel. It reflects light from the large, sliding door that is open to the deck, yard and hovering thunder clouds.

An active painter lives here.

And then there are the guitars that bookend the couch. The baby grand piano that sits nearby. The sheets of music on the piano top, and the music stand near the open back door that holds more, including music of the virtuoso classical guitarist John Williams.

There’s the desk-and-chair workspace tucked in a corner. Book shelves adjacent. And a railing, a functional sculpture of steel, that surrounds the two open edges above the basement stairs.

A painter multi-talented creator lives here.

More than one, actually. Alain and his wife, Maria Navaratne, are the creative inspiration that founded and fuels E11 Creative Workshop in Manitou Springs, now located within the Manitou Art Center campus between 513 and 515 Manitou Avenue.

They started the preschool more than a decade ago, with their son Jules, now 13, as the first student. The school, in fact, started down their basement stairs, past that sculpted railing. Their daughter Agnes, who also has grown up with E11’s influence in the family, recently completed her freshman year at the University of Colorado-Colorado Springs, where she studies Game Design + Development.

A family of creators lives here.

The Elements of Creativity

A Sri Lankan father. A French mother. Born in London, Alain’s early childhood was lived in Sri Lanka, making Sri Lankan his first language, and one he’s since forgotten. At seven years of age, Alain moved with his family back to London.

A student of sculpture at Middlesex University, and a truck driver during school breaks. “I liked getting paid to bum around Europe.” Portugal, Spain, France, Italy, Greece, Germany, Poland.

Then a family. Then a family leap. By 2002, Alain had long known his wife Maria, and they had a young daughter. They chose to try something new, in Los Angeles. “It didn’t work out. It just didn’t work out.”

Then, Manitou Springs. Started a trucking business. A trucking business curtailed by deep economic recession. A preschool started by Maria in their basement. A preschool that outgrew that basement and has become the go-to for young children to learn through the medium of creative exploration.

Life’s path. For some, it’s clear, black-and-white, direct, settled early on. For others, it’s an ongoing adventure that spurs itself with past, present and bold openess for what’s to come.

Alain has welcomed the wander.

Humanitou: You studied sculpture. How did you arrive at painting?

Alain: The good thing about the college I went to was you could explore. You could go there for printmaking and come out a filmmaker or a dancer. It was all under the umbrella of fine arts.

I like things in 3-D, the feel about them. I see things in 3-D mostly. Those are the things I explored. At the time, I was into kinetic sculpture and installations.

Your paintings have a three-dimensional aspect to them.

It’s tied to everything we do at E11 with the children, where we set out different areas of materials every day. The children respond to the materials. They can choose what they want. It’s not predetermined for them. They can grab materials from anywhere and do what they want, follow their own ideas, see where they take them.

With my paintings, I don’t come at it with an idear of what I want to do.

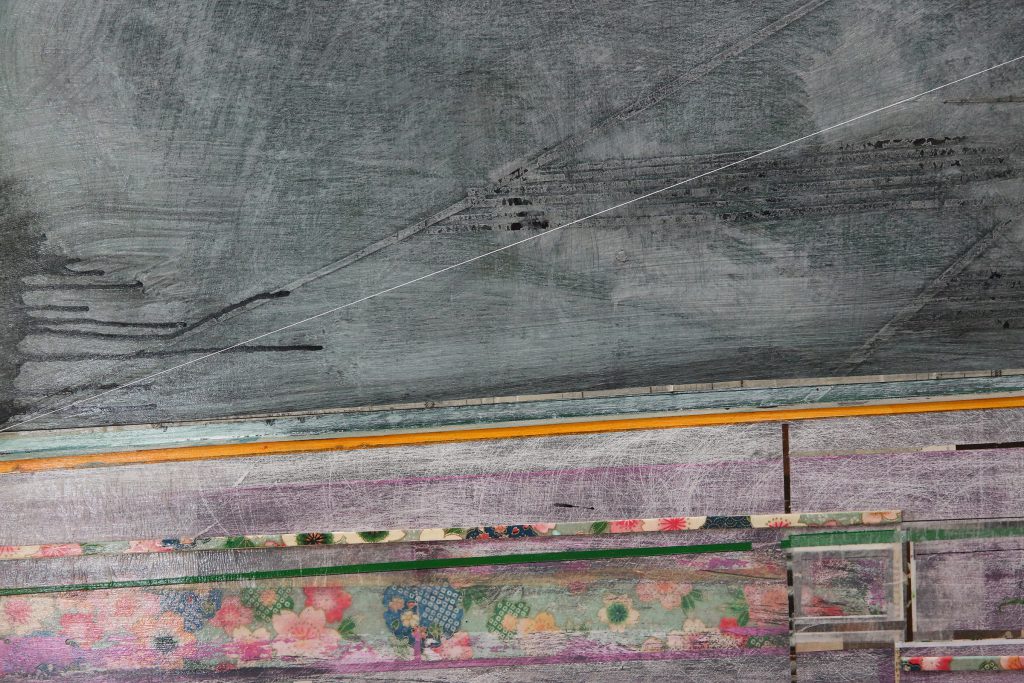

I start by taking a piece of paper or wood or something and applying it, then go from there through a process, seeing how it develops. The materials I use … I like to use typography, old maps, magazines.

I’ll take out anything recognizable about them. I don’t want people to be able to read them. I’ll cut out a thin strip to use as a line. When you put that on the board, it already starts questions in the process like, “Where are you going to go now?”

Sometimes I don’t like something I did, and I wipe it clean and do it again. If I like something too much, I take it off, I get rid of it. If I like it too much, it feels like it’s too easy. If it feels like second-nature, like riding a bike on a route you know very well. That feels like I’ve been there before. I like to get myself into trouble, you know, and figure out my way. It’s a process I go through to arrive at something.

But I prefer to talk about ‘making things.’ I don’t want to call what I do sculpture or painting. I’m a maker. To call it sculpture, that’s pigeonhole stuff, you know? You tell people you are a sculptor, they start asking about what medium you use. You say you are a painter, and they start asking, “Do you paint in oils or watercolors or what do you do?”

I don’t like those constraints. I make things. I want E11 to be a makerspace.

What else do you make or have interest in making?

Do you know what intaglio printing is? It’s a process of printing on copper plates. There are different ways of doing it, but you scratch or mark the plate, apply a resist, and use acid to eat away the scratched areas. Then press the copper plate to print the image (onto another material, like paper).

I had done intaglio printing 25 years ago in college. I had wanted to get back into it but had a fear. It took me until last Saturday, when a parent said he wanted to do it. I joined him as a way to try it again.

What was the fear?

I was 18 when I first did it in school. As an 18-year-old, there’s the whole world to explore and this was just one area. It didn’t make a big impact on me at the time. Now, as an adult, I put a lot more careful thought into it.

And? How did it go?

I love it. I love it. It’s a process. Copper printmaking is a 400-year-old method. Anybody who wants a quick result, this ain’t it.

I want to get more plates and explore doing this and reproducing endlessly. That’s what I’ve learned in my years since college. You can keep going with an idea. There is no end to it.

Alain showed me a plate, what he’d made in his first attempt in 25 years. He’d printed a portrait of a young woman, his mother, in black and white.

(Sitting at the edge of the couch, evaluating his print with care, running his fingers over it.)

It’s tactile. There’s a process when you ink up the copper that is exhausting. It’s all very physical. Much like being a sculptor, as opposed to painting, unless you are a painter like Jackson Pollock.

Intaglio (/in-TAL-ee-oh; Italian) is the family of printing and printmaking techniques in which the image is incised into a surface and the incised line or sunken area holds the ink. It is the direct opposite of a relief print.

At one time intaglio printing was used for all mass-printed materials including banknotes, stock certificates, newspapers and magazines, fabrics, wallpapers and sheet music. Today intaglio engraving is largely used for paper or plastic currency, banknotes, passports and occasionally for high-value postage stamps.

And you play classical guitar? How long have you done that?

I’ve played since I was 35 years old. I had two sisters who always had been musical, but I hadn’t taken to music. I once learned how to play trumpet a little bit as a kid, but that … (Alain laughs off any significance in that effort).

My older sister died, and I got her guitar. But I am left-handed, so when I started playing, I played it upside down. Maria bought me guitar lessons when I was 35.

What are examples of classical guitar we should know of, someone you like?

(He points toward the John Williams music book on the stand across the room.)

His “Cavatina” in the movie the Deer Hunter is an example. Andrés Segovia was the one who first made classical guitar well-known.

If there was only one type of music I could listen to all day, it would be classical guitar. I’m not interested in rock guitar or anything else.

How do you juggle everything? This one is a question of personal interest. It seems as if many people have one passion they commit to — career, sport, whatever — and I wonder about how best to live, or view living, with so many interests, making the most of each. Do you have any wisdom on how to live that out?

I often make art while at E11. But I’m careful about the art I make in front of the kids, when they are trying to make their own. You don’t want to scare them off by them seeing something fancy. So, you’ve got to keep it cool.

I often am working on three or four paintings at a time. If I hit a place with one that I’m not sure where to go, I go to a different one. That can help me to figure out where I want to go when I go back to the other painting.

With guitar, I sometimes think, I’m 52 years old, how am I not better than this? But I think the trick is to not aim, instead to think, if I didn’t know what I do about playing guitar I couldn’t even do what I’m doing.

Overall, I think I still don’t know what I want to do. I never had any direction; I’ve floated around through life. I’ve just always thought in a creative way, rather than mathematical.

And for me, that’s great, because I don’t have to justify my path in a certain direction. It’s all a creative path, whether I’m playing guitar or gardening or building a deck.

If I still lived in London, I don’t know what would’ve happened, but I probably would just be working a job to pay the mortgage.

That’s what’s great about Manitou. You can take a chance and come here, not knowing what you’re going to do or where you’re going to go, and you can reinvent yourself. You can be who you want to be. You’re surrounded by creativity here.