Overview: In this episode (ep 136), Adam Williams weaves stories of his two young sons throwing head locks and left hooks, and finding confidence amid their tears and rage, with his own challenges as a boy raised to never fight.(Released on podcast on Feb. 11, 2023)

Also on Apple, Spotify, Pandora, Stitcher, YouTube, Google and other players.

EP 136 SHOW NOTES, LINKS & TRANSCRIPT

Connect with Adam Williams

Humanitou on Instagram: @humanitou

About Adam

Artwork

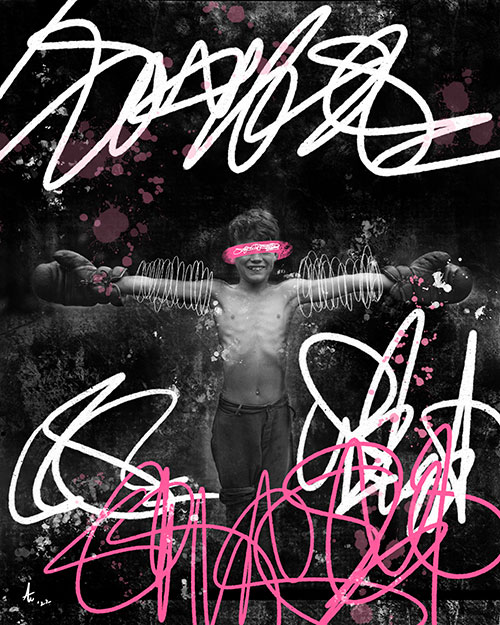

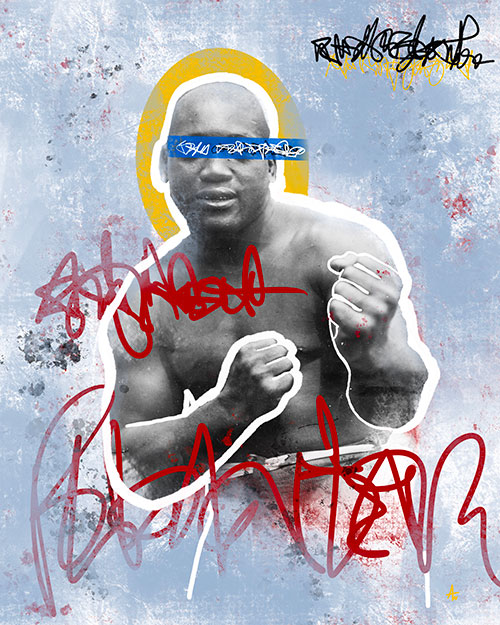

Podcast cover art & art below: Adam Williams

Music

“Old Rope” by Joe Johnson | joejohnsonsings.com

Original Written Version

When I heard the thumping and the bumping just on the other side of the door that stands between our utility-slash-laundry room and our garage, I went to see what was happening.

More than two years into family self-isolation in response to the covid pandemic, a length of time I’ve since come to feel was far too long and not without its emotional and relational consequences, I opened the door to the garage and was in an agitated mood. I wanted just to stop the disruption of my quiet more than I cared to resolve yet one more conflict between my two sons.

I only wanted to push the boys, I’ll just refer to them as “Big” and “Little,” onward and outward into the sunshine for their daily dose of, quote, outside time. After years of being together virtually 24/7, and years of brothers bickering, I no longer had much capacity to care about the reasons for the thumping and the bumping.

I opened the door from laundry room to garage and saw the two boys tangled in brotherly battle in a 2 ½-foot by 4-foot-ish rectangle of space where as a family we layer multiple seasons’ worth of jackets onto coat hooks by the door. And we drape our winter’s snow pants and summer’s wetsuits over a wood railing. And we kick off boots and trail shoes and sandals more or less near a shoe rack, all at the top of a half-flight of stairs that run down to the cement garage floor.

In this tight and untidied space, the older and bigger of my sons had the younger and smaller one in a headlock, his right arm not necessarily squeezing the younger’s neck in the crook of his elbow, so much as restraining him neckily, holding him back, surely sensing his little brother’s face was red with fire and his fists were loaded with determination to retaliate, as is his way.

As is Big’s way, my first born, his sensitive way of not trying to fight his little brother, he looked up at me, his blue eyes asking if I was going to stop this.

And as I had so many times before, I gave them both a tired, “Knock it off. Just go outside.” Big relented, releasing Little’s neck and stepping back, trusting his brother would do the same. He did not. Sensing the easing of his opponent’s guard, Little shoved Big brother with both arms, and it was clear that was only his opening salvo. I mean, as is his way, he was cocked, locked and ready to rock.

“Courage is in Short Supply” by Adam Williams

Big swung once, to keep the impending onslaught in check. Then he paused, again looking my way with expectation that I’d intervene. Because, yeah, I had so many times before. I was out of energy for it this time. Just done.

Little launched a left foot into Big’s midsection. And I said, “Defend yourself. Neither of you listened when I said to stop. … So go! Get after it!”

In the fog of Big’s indecision, Little got the jump. He threw a left arm up and around Big’s neck, getting his own headlock into position. It meant pulling Big, who is taller, down at an angle. Big no longer could even look Little in the eye. He was at a disadvantage.

“Defend yourself!” I said again. “Hit him!”

Okay, I get that that’s not what a lot of parents would do at that moment, not what they would say or, I suppose, encourage. I’ll guess especially not a lot of mothers, and probably not a lot of fathers, either. But sometimes parenting comes down to feel, don’t you think? Feel that sometimes is mixed with a solid amount of fatigue with the bullshit, among other things. And of course, if we were training in a boxing gym, it would be the norm and would be shouted over and over and over.

As a dad, I teach my sons like I might not be around tomorrow and beyond to keep teaching. When I’m gone, and I hope it’s not for another 40 years or so, I want to be around for a good portion of their adult lives, but when I’m gone, should that be sooner than later, I want them to know they had a dad who taught them, who imparted values and meaningful threads for contemplating and living life. I want them to know that even when I’m gone, I’m still with them through what they carry from what I taught.

I also know that Little is a spitfire who has never backed down from his big brother and he’s not afraid to get rough. While Big is untested as a fighter. He’s a sweet, sensitive, highly intelligent boy. And I love them both beyond description. My teaching, and I think my wife more or less agrees, is that our sons need the lifelong lesson to not fear setting boundaries with others, and to not fear defending themselves when needed.

We make it clear that they should never bully others, and should not start fights. But when a fight comes to them: Fear not, handle yourself. You might get in trouble at school, sure, but you will not be in trouble with me, if you’ve done right in defending yourself with integrity and/or someone else who needed your protection.

When I was a kid, I was taught in no uncertain terms never to fight, never to fight. And that if I got into a fight at school, I would be punished there, of course, and again at home. It was a rule of the house, sternly given through a binary, black-and-white lens: fighting is bad, and not fighting means staying in good graces, being a “good boy,” avoiding punishments. Regardless of circumstances. No nuance, no conversation. Don’t fight, or else.

As a boy growing up, as a boy, that was crippling, emotionally and socially. There was no nuance to that rule, no stipulations or if-then caveats. And fear was instilled in me. I avoided fights. I always managed to talk my way out of them, or as we got older, friends were quick to intervene on my behalf, to put the aggressor in check or, had it ever been necessary, even fight for me. Both paths, talking my way out of fights and feeling overly protected by peers, were demoralizing, esteem-crushing and weakening to me.

When I was 11 years old and in sixth grade, our P.E. class was sitting in our assigned auditorium seats after class, waiting on the school bell to dismiss us to the next period. A sizable eighth-grader who sat next to me everyday at the end of class, and who I am pretty sure had been held back at least one grade before, punched me in the mouth. I don’t remember why. But he was a bully, and I don’t recall having done anything to provoke it.

I still remember the numbness in my jaw from that punch, though. And the embarrassment when moments later the bell rang and we were heading out of the gym, and one of my good friends, JP, who I’d known since pre-school said, “Why didn’t you hit him back?!” He was beyond perplexed, couldn’t understand why I didn’t swing, why I just took it and stood there, looking at my attacker wide-eyed and speechless until the bell, mercifully, rang moments later.

“Fuck Around & Find Out” by Adam Williams

This was the same friend, a farm strong but typically very mild-mannered boy, who somewhere around this same age in our lives, fought a bully who was at least a few years older than us who had been picking on both of us. It happened in JP’s backyard.

When JP’s mom, who was in the house, heard ruckus and came outside on the second-floor deck and looked down. What she saw was JP, legs straddling the midsection of the bully, and his fists flying, relentlessly pounding on this kid with alternating rights and lefts.

I thought for sure JP was in trouble. But when his mom started yelling, I realized that she was yelling at the bully, not JP. She was yelling at the bully who was getting his butt beat by her son. “You stop picking on these younger boys!”

When we were older, college-aged, JP would come to the rescue again when the two of us and a third lifelong friend since preschool, were roommates in a duplex apartment. A very angry guy came looking for his girlfriend. I’ll say she wasn’t in my room, and that’s true, but it was JP who we woke up and told to answer the door when that guy came back the second time after I, a very nervous and untested fighter, tried to distract and outwit him by giving him directions that sent him across town to a bogus location that would give us time to get the girl out of our apartment. He went, but he also came back. And JP handled that one.

As a teenager in high school, I found that in sports, I could be a fighter of sorts, within the context of the sport’s rules. Basketball was my love. And on the court, I was physical. I could take an elbow to the mouth, throat, eyes or a gash to the skull that would need stitches, and I loved it. I’d give it back … again, in the context of the sport’s rules. That context was the difference. I knew how to play physically within the sport’s boundaries and not veer into extracurricular, dirty, cheapshot kinds of play.

Off the court, though, that inflexible, un-nuanced house rule against fighting kept me from developing such contextual rules of engagement for myself in the larger world. It kept me from knowing how to set and apply boundaries with other boys, with aggressors testing me.

I never learned through experience how to discern when to stand up for myself. And when I did stand up for myself, I didn’t know how to self-regulate the force of it. Even verbally. So I tended to either overreact or underreact. And I developed real, lasting anxiety and self-esteem challenges around it all. And I’m still not necessarily sure how to strike appropriate balance in a response to disagreement.

When I was in my early 20s, I had become so angry and so deep in alcohol and toxic relations, and a lack of love for myself and understanding of myself. I felt stuck in the Army. I couldn’t get out. But I did have consistent money, an Army roof and chow hall to give me the basics, and a willingness to spend most of what was disposable income at bars, where I also could lash out when the impulse and the perceived opportunity for conflict collided.

Yet I still couldn’t actually get into a full-on fight and test myself. By that point, I think would-be opponents thought I was too unstable to mess with, too “don’t give a fuck.” That was somewhat true. I’d spoil for a fight, to get my ass kicked as much as any other reason. But no one gave me what I was asking for, not what I thought I was asking for.

I could go on. There are plenty of stories. But I think what I’ve said serves as enough … well, context.

As a father, I don’t want to emotionally cripple my sons’ understanding of themselves and their boundaries, and their capabilities. I don’t want them to go looking for toxic tests, or to think they deserve beatings or need to give them, physically or emotionally. I want them to feel their strength within, to love themselves and have the confidence to know that they can handle whatever and whoever comes their way.

“Not Everything Has to be a Fucking Fight” by Adam Williams

I want them to be like some of the self-confident, self-assured men who I challenged many years ago in those bleaker moments of rage and self-loathing as a drunken 20-something, and know that they can defuse, de-escalate and walk away as the more righteous humans of the moment. Not because they fear they’re weak, or that others will think so, but because they’ve established their senses of strong, of what strong is, and know that walking away works when you don’t do it from a place of fear, misguided ego and self-disgust.

And while my sons are still kids, I want them to know that they won’t get in trouble with me as they figure out those truths and boundaries for themselves.

When Little had Big in a headlock in that 2 ½-foot by 4-foot fighting ring at the top of the steps to our garage, I told Big, my sensitive, sweet first born son, “Defend yourself. Hit him.”

Because look, I knew Little could take it. But I wasn’t sure Big had the belief in himself to give it.

I was right. And I was wrong.

With his head locked in Little’s elbow and his upper body bent at a disadvantageous angle, Big let a left hook rip the air. His knuckles landed as squarely against Little’s right cheek as any boxer could hope for, even with a proper view of the target.

And with that one swing, the fight ended.

The three of us went into the living room, both of them crying, not because of the physical altercation so much as the emotional release of it all. It was then that I asked them to tell me what it was about. I don’t even remember what they said now. Typical unmemorable sibling conflict, I’m certain.

But what I absolutely remember was what came after we squared away the feelings of the misunderstanding that had escalated: There was frantic, giddy post-fight analysis.

Tears turned to smiles. Adrenaline fueled the banter about how exhilarating the experience was. “Exhilarating.” That was my then-9 year old’s description for it. He was so stoked that he’d “finally” been punched in the face. “That’s no big deal! That doesn’t hurt!” He was thrilled. He learned that it didn’t hurt in the way someone who has never taken a punch presumes it will.

And my then 11-year-old, he was so excited that he’d found that spark and confidence in himself to feel what it was like to give a punch, because he’s taken many, many from his little brother. He started talking about finding a boxing gym so he could practice. And so he could ride this high of confidence.

There was joy and there was laughter in the wake of the fight. Both boys felt good about themselves. Both boys got what they needed from it. They celebrated it together.

And while my approach as the parent involved there might be viewed as unconventional by others, or worse, I don’t know, I couldn’t have felt better about my sons’ shared experience either.

It’s not the last time they’ve squabbled or thrown hands. I mean, we took them ice skating recently and, at one point, my wife and I look across the ice and they’re throwing punches at each other while holding onto the railing with their other hands. Like they’re damn hockey players, or something.

But then I looked out in the middle of the rink, only 30 feet away from our sons’ public demonstration of brotherly love, and I saw two other young brothers swinging on each other, and then one grinding the other’s head into the ice.

And I heard a woman nearby say, “They’re always fighting.” Then she walked away and sat down.

I laughed to myself. I felt vindicated and not alone, and I felt joyful in the connection.