Jack Kerouac seems to get the most attention of the Beat poets and writers. Allen Ginsberg is like the Paul McCartney to Jack’s John (or is it the other way around?). But Lawrence Ferlinghetti was always there. A presence.

That’s how I perceived it anyway, though I never quite seemed to be able to put my finger on what Ferlinghetti’s presence was exactly. He was of the Beats but kind of wasn’t.

In the New York Times’ obit on Ferlinghetti, who died at 101 last week, the writer, Jesse McKinley, called him “the spiritual godfather of the Beat movement.” And immediately I thought, “That’s it. Those are the words.”

Ferlinghetti seemed to me to be a steady hand and advocate in the Beat’s frantic lives, a man who offered a warm door for Kerouac, Ginsberg and the others associated with the group: William Burroughs, Gregory Corso, Gary Snyder and, of course, Neal Cassady, among other crystallized members and fringe characters.

Like for many readers and spirits wild and/or wishful, my entry to the world of Beat literature was through Kerouac’s On the Road. Generations have carried that book as a vagabond’s bible, in heart if not rucksack, across the U.S. and the world since it was published in 1957.

I was in my mid twenties before a fellow soldier handed me her copy in the barracks in Seoul, South Korea 20 years ago. It immediately influenced how I thought of my experiences riding the rails of Korea, a black ruck on my shoulder, harmonica in my pocket, pretending I did not have to return to the strictures of uniform at weekend’s demise.

In the village outside my rural post an hour south of Seoul, there were little shops that made custom clothing, and would customize American sports apparel. I had Kerouac’s name and the number 57 put on a Kansas City Royals jersey.

In the village outside my rural post an hour south of Seoul, there were little shops that made custom clothing, and would customize American sports apparel. I had Kerouac’s name and the number 57 put on a Kansas City Royals jersey.

The following year, while wearing that jersey as I meandered through the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., a man I never saw before or would again, a man a generation older, at least, recognized the name and number I was wearing. We briefly chatted, bonding over Beat literature in the hallowed halls of Babe Ruth and Joe DiMaggio, et al.

And I associate Ferlinghetti with this string of experiences and memories. Because, in that special way I couldn’t always clearly define, he was associated with the Beats, with their flying spirits, with the whole of creative expression and voice, and so much else.

Though, he always felt like a relatively more mature, together, stable aspect of that group he wasn’t completely a part of. That is, as best as I could tell in my perceptions from afar, and as a layman reader who has casually absorbed the stories of these storied figures over the years.

Ferlinghetti did not take up residence as a central character in their stories of adventure and mischief (and misdeeds) in Tangiers and Mexico City, New York and Paris, and the vague rambles between. But as the pseudo-fatherly figure, or godfather as it were, who would welcome them home when they ventured into his port.

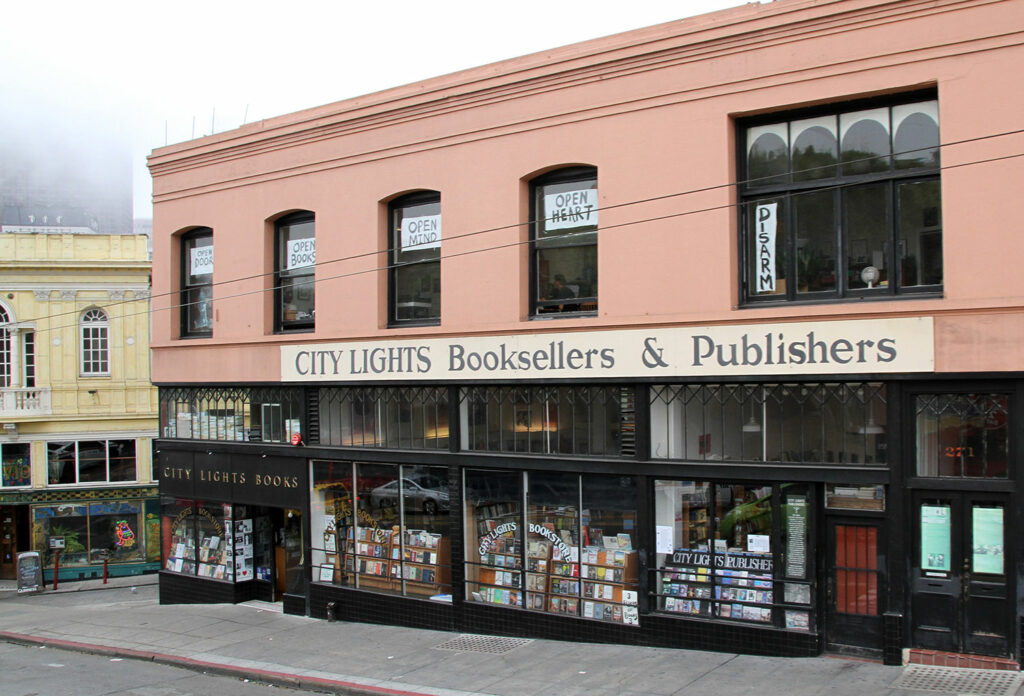

Eventually, I made my own way to Ferlinghetti’s landmark City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco. I had lived within reach of it for most of two years prior to my introduction to Kerouac in Korea. Unwittingly. So it would be many years more before I crossed the threshold of the bookstore that became an anchor in the Beats San Francisco lives.

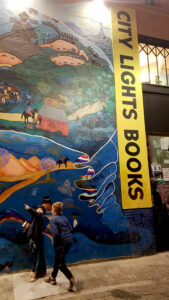

Whenever I have gone back to San Francisco in the years since my awakening to City Lights, I have returned to that corner of Columbus and Broadway (and with Jack Kerouac Alley outside its door). I have bought books and blank journals, and tried impossibly to imagine all that has happened there.

A few years ago, my wife, Becca, and I took our two young sons on what still is my most recent visit to City Lights Bookstore. Our boys have no idea of City Lights’ cultural and literary significance, of course, not only as a bookstore but as a publisher.

But while we were there, our then 6-year-old son went upstairs to the modest-sized poetry room, where readings still are performed to audiences that fill the space wall to wall, and dripping down the stairs (I happened onto one once, and couldn’t get more than halfway up the stairs to see who was there … was Ferlinghetti there, by any hope?).

I walked up the stairs to see that it was our younger son who was engaged earnestly in a philosophical discussion with a wanderer whose voice I was hearing from the floor below, and who had set his backpack down — a young man influenced by Kerouac, it seems safe enough to presume — to take his time.

In that, is the essence of City Lights Bookstore and Ferlinghetti’s ambition when opening it with Peter Martin in 1953: community and intellectual stimulation, a place to spend time.

As Ferlinghetti told the Times in a 2007 interview, and which you can watch in the short documentary (11 minutes, 11 seconds) published last week with the newspaper’s obituary, they wanted people to loiter and read, to be there, to spend time expanding their consciousness.

“Right from the beginning we had poets and writers dropping in, ’cause there was nothing else like this,” Ferlinghetti said. “If you walked into any other bookstore in town, you couldn’t just sit down and read. A clerk would be on top of you.

“We actually ignored the readers. We ignored the customers. You practically had to hit the clerk over the head to buy the book.”

And City Lights endured. For more than 60 years. And then last year the pandemic brought into question many things for City Lights and its staff, as it did for many people and businesses everywhere.

A call went up along with a GoFundMe page in April 2020, letting a global audience, lovers of City Lights and all it represents, know it was in need. Donations flooded in, our family’s donation among them, far exceeding the ask.

During the initial hours and days, I enjoyed reading messages posted for those concerned by Elaine Katzenberger, Publisher and CEO of City Lights Booksellers & Publishers. I especially enjoyed reading that she would visit Ferlinghetti in North Beach with updates.

In the rush, in a matter of hours really, it became clear that his life’s work at City Lights would continue to endure through this exceptionally dark moment.

For the young or uninitiated, it’s more than worth noting here that he was not only a bookstore owner and publisher of poets. Ferlinghetti was a poet himself, a painter, an activist and, I’m sure, much more.

Only three years into the City Lights venture, in 1956, Ferlinghetti published Ginsberg’s revolutionary poem, Howl And Other Poems. As the publisher, Ferlinghetti would be arrested on charges of obscenity for the poem’s references to illicit drugs and lewd behaviors, homosexual and otherwise.

Ferlinghetti won the case, not only for himself, City Lights and Howl, when California State Superior Court Judge Clayton Horn decided the poem was of “redeeming social importance.” The trial established a precedent for freedom of expression in this country, and ignited Allen Ginsburg’s future.

With that alone, recognizing Howl as revolutionary and worthy, publishing it, come what may and then standing up to what did come, Ferlinghetti changed our world.

Of course, I’m sure there are countless other moments, publishing decisions, and strokes of poetry and paint brush that have had an impact on countless souls. (Again, the man lived to 101!)

He was older than the Beats he so often is associated with, though he has said he saw himself more at the tail of the Bohemians than a writer of the Beat Movement. And he outlived them all. Or almost.

Wikipedia tells me that Gary Snyder, for one, still is on this side of the river, at 90 years old. Though, come to think of it, while there were spiritual intentions in much of Kerouac’s work and in Ginsberg’s meditation and chanting practices, Snyder, perhaps, took it the furthest. At least, in a formal sense. He spent years traveling the world studying Buddhism.

Still, perhaps Ferlinghetti’s longevity is fitting enough, if not predictable. If he was more spiritual guide than manic practitioner — with speed-fueled road trips and furious writing binges which, for example, are part of Kerouac and Cassidy’s legends — then it stands to reason he would also come to bear the burning out of these fellow literary’s flames.

Throughout the years, I have been touched again and again by Ferlinghetti’s work, as publisher and poet. Not only by his printing Howl as the fourth in the City Lights Pocket Poets Series, but at least as importantly for me his publishing of Antler’s “Factory” (1980), number 38 in that series.

Antler wrote “Factory,” a 61-page poem, over a period of four to five years (1970-1974). And though I did not work in a factory when I found Antler’s poem (and never had), I was a young man feeling pent up in cubicles, and by corporate status quos, and by fears of life seeping away if I stayed that course. The poem resonated with me nonetheless, as Ferlinghetti knew it would for many.

The opening lines of section VI of “Factory” (p. 26):

Millions of humans enter factories at dawn.

How many have their arms raised to the sun?

How many want to be late? How many demand to be fired?

Faces leaving as I arrive, faces arriving as I leave —

(Am I not also singing — “I have to go and die some more

so that my corpse can live?”)

And in Ferlinghetti’s collection, A Coney Island of the Mind, (1958) which I picked up from the rummage table of the Taos (N.M.) Public Library while having my own On the Road experience of sorts in my 1975 VW bus named Boio some 15 years ago.

It was the 8th edition of the slim paperback poetry collection. I did not know it was one of the most popular poetry books of all time. I liked its vintage black-and-white cover, its title, and, aware of the Beats by this time, its poet.

So, dimming the lights now on these reflections, some of Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s words … Here are opening lines from two of his poems published in A Coney Island of the Mind.

From No. 15 (p. 30):

Constantly risking absurdity

and death

whenever he performs

above the heads of his audience

the poet like an acrobat

climbs on rime

to a highwire of his own making

and balancing on eyebeams

above a sea of faces

paces his way

to the other side of day

And from a poem Ferlinghetti published in 1955, in his book, Pictures of the Gone World, some poems of which he also included in publication of A Coney Island of the Mind, No. 11:

The world is a beautiful place

to be born into

if you don’t mind happiness

not always being

so very much fun

if you don’t mind a touch of hell

now and then

just when everything is fine

because even in heaven

they don’t sing

all the time

Rest now, Mr. Ferlinghetti.

IMAGE CREDITS

1. Title photo by Christopher Michel, via Wikimedia Commons (Ferlinghetti at Caffe Trieste, 2012)

2. Screengrab of New York Times video (click image/link to watch at nytimes.com)

3. Author’s sons in Jack Kerouac Alley, outside City Lights Bookstore, 2018

4. “Stash Your Sell-Phone” sign hand-painted by Ferlinghetti; photographed by Adam Williams (author), 2018

5. City Lights Bookstore photo by Tony Hisgett, 2014, via Wikimedia Commons