Humanitou hosted a pop-up event during Arts Month as part of ArtPOP, a local-arts series supported by the Pikes Peak Arts Council and the Cultural Office of the Pikes Peak Region. Participants shared stories and were photographed during 30-minute sessions. The conversation below is one of seven in the Humanitou ArtPOP series.

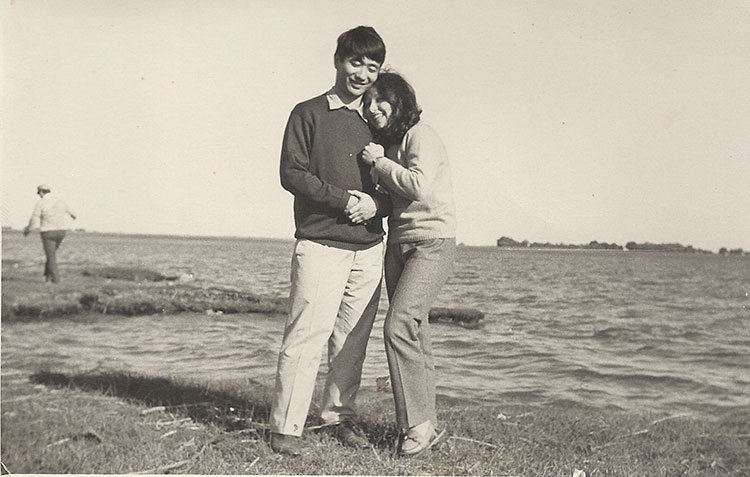

Gaby Oshiro is an artist who, in recent years, has started giving voice to a heart-rending story. It’s one she held deep within for nearly 40 years.

Born to a Japanese father and an Italian mother in Buenos Aires, Gaby was a little girl when a military coup d’etat overthrew the Argentinian government in 1976.

In the wake, her father, a lawyer fighting for workers’ rights, would become one of 30,000 people to be disappeared, people known as desaparecidos. He was one of 17 Japanese to be taken.

When Gaby sat with Humanitou, she shared her memory of the night her dad didn’t come home for dinner, and how she hid the truth from classmates and friends until, in her 40s, she started to unpack it all.

Now, through her artwork, she shines light on not only the 17 Japanese who were taken, but the impact on their families.

Meet Gaby Oshiro.

Humanitou: When you applied to be part of this Humanitou ArtPOP experience, you mentioned your father’s disappearance under military dictatorship in Argentina. What would you like to share about that now?

Gaby: The military took the example of Pinochet in Chile. He did everything in the open, but the difference with the Argentinian military dictatorship: they did everything at night.

They overtook the government while everybody was sleeping. In the morning, everybody was like nothing happened, nothing to see. They kept everything they were doing in the shadows.

Since everything was hidden, I had to go to school and I couldn’t open my mouth and say, “My father has disappeared.” All of the sudden this person disappeared from your life and nobody knew where he was. Nothing.

They were taking all these people to different centers, concentration camps, and they were torturing and killing them. Or grabbing them and throwing them into an airplane and then throwing them out in the Rio de la Plata, a river that is in Buenos Aires.

If you didn’t have anybody close to you who disappeared all of the sudden, you didn’t know people were being taken and killed.

They had these black Ford Falcons. These guys were all dressed in civil clothing, not military or policemen’s clothing. They were armed.

He had the chance to exile to Mexico. He said, ‘This is my country. I’m going to stay here and fight.’ For a long time, I was mad at him.

I went back to Argentina in June and they had discovered new places where they were keeping people that had been kidnapped. They were in the middle of the city. It’s not like they were outside or in an isolated place. They were right there with houses all around.

I happened to go to one of these huge escuelas, a school for the military, and that was a museum. It’s called Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada. This is in one of the nice areas of Buenos Aires, and they had an area where they’d keep people they were kidnapping.

They also had on the top floor all the women that were pregnant. They would have the babies and then the military would steal them and adopt them themselves, and never tell them who their parents were. We’re still looking for these kids.

This is not something that is far away history, like the military is gone and we’re done. Two months ago they just found another of these children.

They also are trying to do it justice and bring all these people that were involved to jail. But many of them are super-old or have died.

Videla was one of the dictators at the time and he was in jail, but many of these guys stay under house arrest. Depending on which president is in charge, they can walk free. You can be on the bus, sitting next to a killer and you wouldn’t even know it.

Humanitou: How old were you when your father was taken? Do you remember the experience of that happening?

Gaby: I was 5. I remember, even though it’s been over 40 years since he disappeared. It was in ’77. I remember my mom was super, super-duper nervous that my dad was not there.

He would come at a certain time and we would all have dinner together. My mom was preparing dinner. I remember she was boiling something. I remember it like it was yesterday. The table was set. We were all ready, waiting for him, but he didn’t show up.

My mom said, “Go to bed.” We didn’t even have dinner. I fell asleep, then she woke me up, me and my brother who was 3, and said, “Let’s go.” We went to my grandparents’ house. They were in the next neighborhood, like 20 blocks away.

My mom was crying. I’d never seen her cry before. Ever. All the sudden she was crying. My grandfather and her, they went to my dad’s office. Then they came back and he didn’t come back with them. She found they’d burnt his office. They stole documents.

My dad had a partner and he was taken with them, as well. They were having a big trial against one of the companies that laid off a lot of workers. My dad’s job was defending the workers. It was all connected.

I kept it all hidden. I didn’t want to look back. I was not even interested in finding out anything, but my dad’s friend, who was another lawyer, when I went back in June I talked to him. He told me a lot of things I didn’t have the courage before to face.

He thinks it was because that company belonged to one of the relatives of the ministry of economics from the dictatorship. So they were going to lose a lot of money if (my dad) won the case.

The thing is it was not just the military, but all the rich families in Argentina, and the Catholic church, as well. They were all hushing everything. It was all about economics.

Many factories, like Mercedes-Benz and Ford, and a whole bunch of multinational companies, had business in Argentina. It was useful for them to keep quiet.

It was ’78 when they had the soccer World Cup in Argentina. A lot of different journalists came to Argentina. My mom and others were handing them letters to tell them what was going on.

Humanitou: You were 5 years old. You’ve not seen him since. I can’t imagine how difficult that has been and, I’m sure, still is.

Gaby: My school in Argentina was super-big. It was a pretty important school, so many children of the military were going to this school, as well. So I couldn’t say my dad was a desaparecido. I had to hide the fact that he was gone and go on like he was still alive.

We’d go on vacation and, “We’re here by ourselves. My dad stayed in Buenos Aires to work.” It was all hiding, unless we knew who was in front of us and we could be free.

My mom always told me to stay quiet and not to let people know. We were kind of lucky, because we were not taken like other kids.

Humanitou: Do you feel like you can express how this has shaped your life?

Gaby: It’s completely scarred me. It’s something I’m still trying to overcome. I know my dad was a lawyer and he fought for justice, but at the moment I felt like he had abandoned me.

He had the chance to exile to Mexico. We went to the Mexican embassy for, like, a month. They were trying to catch him before, but he escaped. He said, “This is my country. I’m going to stay here and fight.”

For a long time, I was mad at him.

Then in 2016, so not too long ago, one of my friends said, “My friend is writing a book about the desaparecidos from the Japanese community. He’s got a chapter that he’s missing.” He asked me, “Do you know anybody who knows this guy? He has your same last name.”

He didn’t know anything, because I wouldn’t even tell my friends. I said, “Actually, that was my dad.” He put me in contact with this writer. I didn’t want to even talk about it. It was like a Pandora’s box, all the feelings you’ve been pushing down. They just come out and I don’t know what to do with them.

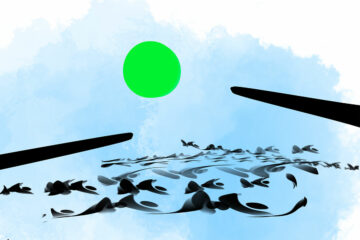

Gaby Oshiro’s installation, “Presence of Your Absence.” Centro Municipal Arte Avellaneda, Buenos Aires, Argentina. June-July 2019

After I helped with the book, I said, “What can I do? What have I been doing all my life?”

I was always painting portraits, so I started painting my dad. Maybe I can do the same thing for all the other Japanese families that lost their loved one.

I did all these portraits. So I did an installation with a friend from Italy. We did an installation with doors, and we were invited to do that at the Library of Congress in Buenos Aires. That was the first show we did about this subject.

I said, “OK. I did it. I told the world that my dad was one of them.” It was like an homage for him and the other 16. And after that I still had things to say about it. So I kept painting them, all 17. I did another show, in Italy, in December 2018 and January 2019.

Then I got the Colorado Creative Industries grant, and I was able to use that money to do another show two blocks away from my dad’s office, the last place he was seen alive. They put a plaque in that building, saying my dad and his partner were taken from that place.

Humanitou: You were upset with your father for a while. Since you’ve opened up to your feelings of this experience in the past few years, have you come to a place of, I don’t know if you feel forgiveness is the right word, but … ?

Gaby: Since I didn’t want to think about it, first you get mad because he wasn’t there. When I think about him now, I understand why he stayed. I would have stayed, too, if I was him. There were all these people who needed him. He wouldn’t turn his back.

It’s more understanding, I think, than about forgiveness. He knew that they were looking for him. He escaped, like, three times. But he wanted to make a difference, so he stayed. It would have been easier to say, I’m leaving, but he didn’t.

If you look up all the people they were taking, they were people that could make a difference. They didn’t take the little person that didn’t know anything, or that was not involved in politics. They took the people that mattered: artists, lawyers, teachers, lots of teachers, and whoever was helping the poor.

One of the Japanese desaparecidos, he was 18. He was buying shoes for kids in the favelas. They’re not even houses. They’re more like huts. They have the poor people all together. And he was going to these places to give shoes to the kids.

My dad told him, “Go to Japan. I know they’re looking for you. I’ll buy the ticket for you.” He said, “No. I’m not leaving until all the kids have shoes on their feet.” And he was taken.

People were taken for printing little magazines; one was of poetry. They killed a singer for singing a song about hope.

Humanitou: How do these things — your experience, your father’s story, what you’ve been learning in recent years — influence your perspective on life?

Gaby: I have three kids and they’re interested in knowing my history, so it’s not that I want to keep it hidden.

I want them to be proud of their grandfather and even their grandmother, because she was looking for my dad for a long time. They both wanted to make a difference.

I’m not into politics but, with every show I do, in Italy or Argentina or wherever, I want to show other people that they were there.

I’m not into politics but, with every show I do, in Italy or Argentina or wherever, I want to show other people that they were there.

And it’s also about the families. Many times people remember the desaparecidos but you don’t remember their families. And I have their support. At every show I had in Argentina, they were there.

I used chairs last time for one of the installations. It was called “Presence of Your Absence.” We stripped chairs; it was just a skeleton at the end. And then I put the picture of them there.

That way you can see the space that they would have taken, if they were alive. The chair was taking the shape of that absence.

Like when you have dinner, that’s where you were noticing the chair is empty. It’s connected with that night. We were going to have dinner, but he was not there. Every time we have lunch or dinner, that chair was empty.

All that silence that we kept, we’re filling it with the artwork. We’re telling all the stories about each of them. With my work, I want to show people that they were loved and we miss them.