From the back deck of Brenda Biondo’s house, there’s a sweeping view of Pikes Peak, the Manitou Incline, and the ups and downs of the surrounding terrain. The blue sky that sprawls above calls Brenda. The light, the color. It calls her with camera in hand.

A fine art photographer born in Queens, N.Y., Brenda grew up in a small harbor town on Long Island, surrounded by woods. City. Not city.

Many millions live in one or the other for a lifetime, never knowing the opposite. Full-on urban or rural. Brenda has known the range and experienced the possibilities.

In Brenda’s family, NYC was a central figure. Her Brooklyn-born father, a photographer, worked in advertising in Manhattan. He often would take Brenda there. But he enjoyed the outdoors and the family often escaped the city, upstate to the Adirondacks.

After college in Virginia, a career kickoff in Manhattan. A move to D.C. that included work trips to Paris. Eventually, Manitou. Perhaps it was inevitable, the city would give way to the not-city.

“When you’re younger, in your 20s, I think you want something a little more exciting like city life,” Brenda says. “I like it calm and quiet and peaceful, and that’s not necessarily, Long Island or New York or my family background. We’re Long Island Sicilians, it can be very loud. I love the outdoors.”

The outdoors is, in essence, Brenda’s muse and material.

Are you a full-time photographer?

This is my third career. I’ve been making pictures since I was 15. I didn’t pursue this until 14 years ago, and that’s when my kids were born. So, I do the kids, the dogs, the house, the landscape … my full time can be two hours a day, it can be eight hours a day.

And I’m lucky. My husband’s job pays our bills, and that’s pretty much why this wasn’t my first career. I don’t know a way to buy groceries being an artist. I never wanted to do wedding photography or any of that stuff, so I couldn’t really figure out how to do photography as a career and survive.

I have a journalism degree and I was in corporate communications for a good amount of my time. I did the photography on the side.

When I hit 40 and my first kid was born, I decided it was really time to do photography full time because that’s really what I wanted to do. Like I said, I was fortunate my husband’s job was able to pay the bills at that point.

You’ve worked as a writer, publishing in various magazines and newspapers.

I went to James Madison University in Virginia and they had a good journalism department. My idea was to be a travel writer, because I loved traveling, I had worked in Switzerland taking care of horses, I loved languages. So, I wanted to be a travel writer.

So, unfortunately, what also happened — I say unfortunately, but it probably worked out in the long run — my last semester at school, I took a public relations course because it was required. I was like, “Oh, this seems glamorous. I’ll work for an international company. I’ll get somebody else to pay for me to go overseas.”

I got out of college and went back to Manhattan, where my parents still were, and I got a job at a P.R. agency. And I hated it, oh my god. My first day, I hated it. I did that for a year and I quit, went overseas for a few months and came back. I moved to D.C. and worked in corporate communications for another nine years.

My last job was with this international, French-owned construction materials company. They were giving me French lessons and I would have business trips to Paris. This is what I would have killed for right out of college, but by then I realized I didn’t want a boss, I didn’t want to do corporate work.

I’d always been interested in environmental issues, so I decided I was going to quit, originally thinking I’d write half-time and take pictures half-time. And then realized there’s no way I can make money doing photography at this point, so I would just focus on writing.

I would shoot some stuff for my own stories, mostly environmental, conservation, health-oriented stories. I got published in the Washington Post and did a fair amount for US Weekly magazine, Nature Conservancy magazine, Solar Industries Journal, stuff like that.

But even though I was a good writer and I liked writing about these issues I thought were important and I liked seeing my work published, writing is so hard. I didn’t like interviewing people. I liked putting information together. That was the part I was really good at, but I didn’t enjoy writing at all, I didn’t enjoy the process.

And this whole time I’d take vacations and I’d continue to shoot, and I’d heard about Santa Fe. This was 20 years ago, 25 years ago. I’d go out on vacation and I’d shoot, and I just loved doing that.

I thought I could be a better a photographer than a writer. I would read stuff in the New York Times magazine and Outside magazine and think, “Oh my god, I could never write like this. I could never write as well as these people.” And I wanted to, but I knew I didn’t have that voice, and I thought I had what it took to be really good at photography.

It was hard. My daughter was a year old at that point, so I had a baby and two years later I had another baby, and I’m trying to do projects and trying to learn how to print and figure out how to make this a career.

It was really stressful. It’s gone well. It was a lot of work, it is a lot of work, but the momentum is there now, and I’m getting really good response to my work and I’m happy with it.

How did you go from writing to fine art photography?

When I switched to photography, I was trying to decide what I was going to shoot. I would have loved to focus on conservation issues but I couldn’t figure out how to do that in a way that I wanted to. I didn’t want to do do straight documentary, “Here’s a picture of a clear-cut forest.”

I almost didn’t switch to photography, because I really thought it was important to focus on conservation issues through the writing, and since I couldn’t figure out how to do it with photography I was almost saying “How can I justify this? I want to do something that’s relevant and important.”

And, finally, I thought, “You know what, just because I don’t know now how I’m going to do that, I’m just going to make the switch and I’m going to assume eventually I’ll figure it out.” I started shooting a little bit.

You have a photographic series that focuses on conservation, but you also shoot abstracts. And you have a book that documented playground equipment.

I’ve always loved shooting abstract stuff. I was at the playground with my daughter and I noticed one of these slides at the playground. It was plastic and the light was coming through it, and I was thinking about shooting other playgrounds in an abstract way. But then I realized that all the equipment that I grew up on, the metal slides and the see-saws, that was not around anymore.

So I started checking out some of the other local playgrounds and I realized there was not much of this stuff left. I realized really quickly this would be good subject matter, because it was Americana, it was something generations of people had fond memories of, it was part of the country’s culture, and nobody had shot it before.

When I started shooting playgrounds, I never thought it would turn out to be such a huge project. And it’s still going on, even though, as far as I’m concerned, I’m done with playgrounds. It’s in a museum show right now, and it’s got a five-year traveling tour.

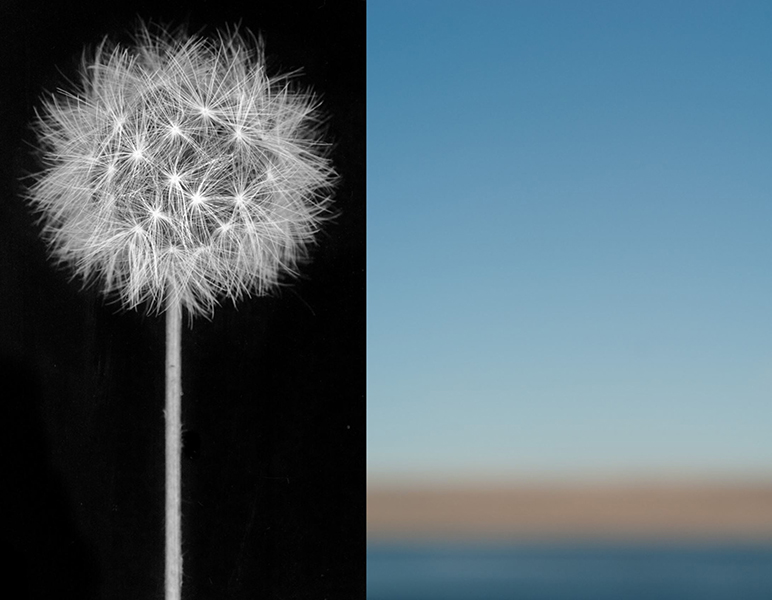

I was shooting the conservation series, Remnants & Revival, and I was trying to figure out the abstract work I was going to do. I was doing Remnants & Revival and I had a few shows with that and, as much as I really liked doing the diptychs and looking at the micro/macro aspect of the environment and thinking about how the landscape has changed even if it doesn’t look like it’s changed much, what I found in shooting landscapes what I really loved shooting was color and light.

I was out on our deck constantly, shooting sunsets and clouds. I love the sky and am kind of addicted to blue sky.

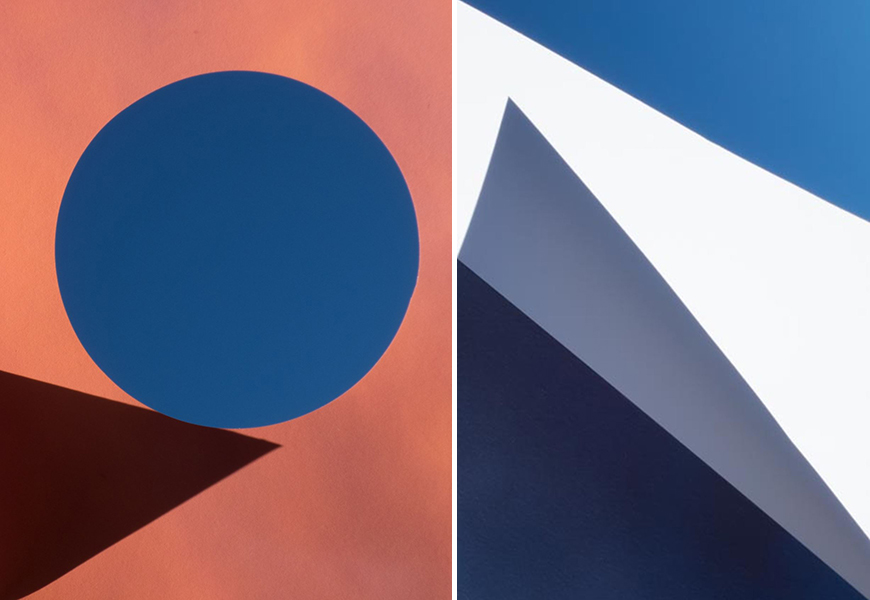

Your Paper Skies series, the abstract nature, looks like paintings. They are not straightforward, not obvious that you actually are photographing the sky.

That took years and years and years of experimenting. The paper skies came out of another series of atmospheric color I was doing where there were also diptychs and closeups of the sky and clouds to isolate the color and take it out of context.

I was having trouble printing the blues. I was getting really frustrated, because when you see the sky on a backlit monitor it glows like it does in life. When you put it on paper, it doesn’t glow.

I was losing all sorts of detail and nuance of the color, so I took this print I was having so much trouble with and came outside and started holding it up and really thinking about what am I losing, what’s getting changed here as it turns from the real subject to a photograph on paper?

As I started playing with these printed photographs and seeing what the shadows did there’s a lot of optical illusion. I try to read a lot about modern art, because aesthetically that’s my big influence. When I took that one art history 101 class in freshman year of college, I discovered Rothko and Frank Stella and Georgia O’Keefe, and these amazing painters. I wanted to create something that, I think, was inspired by that type of artwork.

Every image is a piece of paper that’s been folded, and I stand up here and re-photograph it. I take lots of different photos and I move the shadow around and I crop. They are super-simple.

A lot of people think they are Photoshopped. They’re photographs of photographs. That’s what I like about it. It’s a really simple process, but it creates something that’s really unusual.

You start with a sunset print that’s this color (demonstrating with one of her prints). By the time I cut a piece out of it and fold it over and get shadows, this is actually the same color as this but it’s in shadow … you start playing with a lot of perceptions and optical illusions.

Your consider your Once Upon a Playground book project to be done. What are you doing now or looking to do?

I’m concentrating now on the abstract work. I really enjoy it. Playgrounds are, I hope, done. I’m also working on another book project that is conservation-oriented, and I decided that I’m going to do abstract work and book projects.

They won’t necessarily be as documentary as (Playground). I think the next ones will be more creative and artistic, but they’ll still have a narrative and talk about something.

What do you think makes art, or even an artist?

I think you just self-identify. If you think you’re being creative and expressing yourself in whatever way you want to express yourself, I think that’s artistic. If you want to call yourself an artist and you make art, whether that’s macrame or it’s pottery or book design or anything you self-identify, that’s what makes an artist.

It could be beautiful or important or interesting, or it could be all three. That’s the one thing for me, I love making the abstract work, I love how it works and I enjoy it so much, it’s really fulfilling but, for me, that’s all aesthetic.

I also want to do something that’s important, that’s meaningful. That’s where the books come in, that’s why I’ve decided to do both things.

Sometimes, people say, “You should just concentrate and focus and build your brand.” And I’m not listening to any of that. I will always do abstracts based on atmospheric color and light, that will be one of my things, and the other thing will be these books.

I haven’t called myself an artist in the past, even though I was shooting. I had these other jobs and I was doing photography for myself. Personally, I felt like that’s not my career, that’s not my full-time focus or majority focus so I don’t qualify as being an artist. But most artists have to have another job, right?

Society often equates personal value to money you make and how you make it. I think that can make it tough to self-identify as an artist.

Right. That’s interesting, because for the first 13 years I’ve done photography, even with the book, I’ve lost money. If that’s what the qualification is, I haven’t been an artist until last year, when I was, I don’t know, $600 in the black, for a change.

My gallery in Denver sells some of my work. I’m looking to pick up a second gallery, in California, hopefully sometime soon, and maybe another gallery in New York in a few years.

I’m thinking five, 10 years down the road I should have an income stream, as I get more shows and I get more known, hopefully, I will have more sales and there will be some legitimate income. I worked 20 years to pay the bills. I had jobs I did not like and some I liked OK. But …

What are your goals? What is the measure of success in your mind?

I ask myself that a lot. Originally, it was to get the book published. Because it was my third career and because I was struggling to find enough time to do it the way I wanted to, and it just took a lot of time and effort and money, I felt like I put myself under pressure to get this book done and prove I knew what I was doing and this wasn’t a flighty thing, and I actually was good at this and knew how to make it work.

I said to my husband after the book came out, “Everything else is gravy.” That was the big accomplishment. The Wall Street Journal wrote about it and, OK, (exhales), I can relax about it.

But then I thought about what do I want to do next, where do I want to go with this?

Now I’ve had my first museum show (Brenda Biondo: Play, San Diego Museum of Art, CA. Exhibit dates: July 2017 – January 2018.), and that was a big thing.

So, now what do I want? I said I want to have a gallery that represents me, so now what?

I think I want to keep making work that people respond to. I want to keep making books that people respond to and are on subjects I feel are important.

The books are important. I feel like I want to make a contribution. If I’m focusing on good, important subjects and presenting them in an interesting way, then I’ll feel really good about that.

This Humanitou conversation is cross-posted at PeakRadar.com. | PeakRadar.com is the Pikes Peak region’s cultural calendar and digital cultural center, connecting residents and tourists with our vibrant arts community. Your source for what’s happening is PeakRadar.com!

This Humanitou conversation is cross-posted at PeakRadar.com. | PeakRadar.com is the Pikes Peak region’s cultural calendar and digital cultural center, connecting residents and tourists with our vibrant arts community. Your source for what’s happening is PeakRadar.com!