Editor’s Note: This profile series called “A Poet Was There” highlights poets from around the world who through their verse convey the kind of intimacy, truth and connection with place and experience that only exists because a poet was there. Read “A Poet Was There: Introducing A New Blog Series” to learn more.

When introducing this blog series, “A Poet Was There,” earlier this week, I wrote of how when I travel, I look for bookstores that carry local poets’ work. I’m kicking off the series profiles here with the late Vietnamese dissident and poet Nguyễn Chí Thiện, whose work and story I encountered on one such adventure.

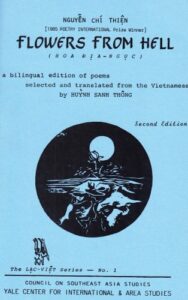

I bought Nguyễn’s collection of poems, Hoa Dịa Ngục (Flowers From Hell) and another book, Scattered Memories, by the late Zen master, Giác Thanh in Vietnam. My wife, Becca, and I were there two Marches before the COVID-19 pandemic.

I am unbelievably grateful for that trip to Vietnam. For me and my family, and I’m aware not all agree, the pandemic has changed travel, especially global travel, for the indefinite future. Years, I think.

Having traveled the world somewhat extensively in our 20s and early 30s, individually and together, that trip Becca and I made to Vietnam had been our first non-work adventure to another country since welcoming our first of two sons to our family nearly a decade prior.

It was there, in Vietnam, that we decided we could no longer wait to give our boys, even now only 8 and 10 years of age, their own opportunities to travel internationally and learn of other cultures firsthand. We had no idea how significant that timing and the experiences, foreign and domestic, we would fit into the next two years would become. For ourselves and for our family.

Now we’re at home, a year and counting. No big travels on the horizon. Though, I feel like I owe this caveat: We live in the mountains of Colorado [Núu-agha-tʉvʉ-pʉ̱ (Ute) land … See “Whose Land Am I On?”], in a place where, as we point out to our sons, other people travel the world to see. We have space, beauty, connection with nature. In that, we’re beyond fortunate.

And living in this rural mountain place, I myself am “a poet who is here.” I see something of my role to connect with this place, and convey something of it as my experience here deepens in the years to come.

Though, I’m hopeful there is a rancher- or cowboy-poet generations deep into this life here who I can find, one whose verse I can jump into. And that of a Ute poet whose line runs so much deeper in this land.

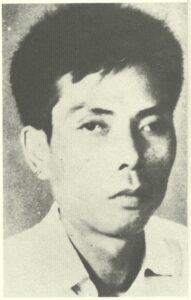

Today’s “poet who was there”: Nguyễn Chí Thiện.

Nguyễn opposed the communist North Vietnamese regime. In 1958, he independently published a review, Vì Dân (For the People). For that, he and two others were placed in a “reeducation” camp. Only Nguyễn survived.

Upon release, he joined an anti-communist movement. Again, he was arrested for a two-year stint of reeducation. Released in 1964, he continued. And then again was imprisoned in 1966, for poems that were irreverent toward the government. This time he would be reeducated for an indefinite period.

That period would end in 1978, however, when the communists released him to make room for new prisoners following the fall of Saigon and the victorious end of the North Vietnamese war against South Vietnam and the United States.

With that release, Nguyễn was denied any opportunity to work by the communists. He sustained himself by letting out his room to prostitutes. With that money, he bought ink and paper, and he finally wrote the many years’ worth of poetry he had composed and held only in his memory. And he devised a plan for getting those nearly 400 poems to the free world.

In February of 1979, Nguyễn rushed into the British embassy in Hanoi, passing communist guards. He desperately handed off his manuscript and a cover letter written in French, explaining his intentions.

The British welcomed him and indeed would help to get his poems to the outside world, telling the story of what was happening under the communist regime there.

An English translation of Nguyễn’s letter, in one long paragraph, which is published with his poems in Flowers From Hell:

It is on behalf of the millions of innocent victims of dictatorship, already fallen or dying a slow and painful death in Communist prisons, that I beg you to have these poems published in your free country. They are the fruit of my twenty years of work. Most of them were created during my years in detention. I think it’s up to us, the victims, rather than anyone else, to show the world the incredible sufferings of our people, oppressed and tortured at pleasure. Of my broken life there is left one dream: to see the largest possible number of men wake up to the fact that Communism is a great scourge for mankind.

Please accept, Sir, the expression of my deep gratitude as well as that of my unfortunate compatriots.

Nguyễn was arrested again upon exiting the embassy.

The British diplomats sent the manuscript to London. A Vietnamese employee at the BBC got hold of the manuscript and sent it to a Vietnamese magazine in Arlington, Va.

Flowers From Hell was published in 1984 by the Yale Southeast Asia Studies program at Yale University. At the time of publication, no one other than his captors knew of Nguyễn’s whereabouts or status. It was named winner of the 1985 Poetry International Prize in Rotterdam.

A few of Nguyễn’s poems, translated from Vietnamese to English Huỳnh Sanh Thông, of Yale University:

“Each Error Cracks the Heart A Bit” (1963)

Each error cracks the heart a bit,

yet time will more or less heal up the wound.

But living on Red soil is a mistake

which time will widen, deepen, with no end.

In all my days, not seldom have I erred:

I have misjudged them, places, moments, men.

the error, tough, that’s ruined my whole life,

was to believe and trust the Communists.

“Before A Poet’s Eyes” (1972)

Before a poet’s eyes

things hover in between what’s real, what’s false.

A pothole filled with rain becomes the sea.

Back stooped over the street,

a rickshaman seems small or looms as large

as all those kings renowned in history books.

A poet give the hookah pipe

immortal life,

can change those lords

who’ve turned the country upside down

to higgledy-piggledy clowns.

In the benighted land,

a poet of this kind

has only his bare hands,

which the police may manacle at will.

To meet such poets, let the world come in

and see a jungle concentration camp.

they’ll read you verse that makes your hair,

not just Ching K’o’s,

stand up and sweep off

all caps with the yellow star

in the jungle night.

“Eyes Shut Tight, I’m Lying Sleepless Here” (1969)

My eyes shut tight, I’m lying sleepless here.

The gong rings loud and long — it’s morning now.

I’m lying still, dead-still — no thought, no dream —

just slumbering in shadows, dready, sad.

Shadows of parents aging, dumb with grief;

in a vast night where flicker dots of fire,

deserted, fit for neither tears nor laughs,

the grayish shadows of some wretched loves;

it’s my own shadow, coughing blood, back hunched.

I open eyes — stark looms the prison camp.

In Nguyễn’s manuscript were 191 poems, including one that was hundreds of lines long, and 188 “sundry notes,” quatrains. Here is one of those notes, number 61:

My life’s a book I long ago put down.

It once had hopes, those sheets all crumpled now.

Let winds blow off the leaves and turn it quick

to its last page, a plot of dirt-brown earth.

Nguyễn was released in 1990. He spent a total of 27 years imprisoned. He continued to write and publish. Later, he would live in France for three years. He died in Santa Ana, Calif., in October 2012.